Lexical Leo challenged the notion of the synonym in his presentation at TESOL France’s conference. Are any two words the same? And of two ‘close’ words, which is the best to choose?

You can take Paul Valéry’s advice:

Of two possible words, choose the lesser

Which is not bad advice for some learners. I recently taught a group of French adult learners on a two day intensive writing workshop. A common problem for French learners is a prefererence for words which closely resemble their own. The problem with that is that English has often added its own twist to the meaning. In this example:

‘I read a good book concerning Wall Street’,

the choice of ‘concerning’ over the lesser word ‘about’, makes this sentence sound rather strange.

Leo demonstrated that there are four distinguishing features between these near synonyms:

And for our sentence here, ‘register’ is one of the problems. ‘Concerning’ is more formal in English than ‘about’. You could look at this in terms of collocation too, for example:

‘we read about this every day’

‘I read a book about that’

I could go on, but to be fair you’ll get a lot more from reading Leo’s presentation yourself. What you might find interesting is how Leo’s ideas work when applied in a Business English classroom.

I had test driven Mark Hancock’s Listening lesson with great success the previous week I thought I would try out what Leo had talked about in my advanced writing class. I made use of Leo’s ‘word pairs’ activity but I created a warm up exercise. I always like to agree the objectives for a class with the learners, but as ‘improve my vocabulary’ is a pretty safe bet,I was able to prepare a good bit of material in advance

I started with the common mistakes like ‘concerning’ and ‘about’. I put up a list of Old French and Latinate words and asked the learners if they could come up with the Old English or Germanic equivalents. It was not much of a challenge for the learners to find equivalents. But then I asked Leo’s question:

Are they the same? Does ‘Introduce = bring in’

and the result:

This was done using examples and the learners own knowledge alone. Once we had exhausted what we knew, we looked at the Cambridge Business English Dictionary Online.

This set up the next activity which was to research the differences between common and close words used in business. We had three teams and each looked at one word pair:

benefit advantage

feature functionality

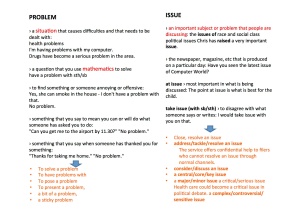

problem issue

Each team had to look at differences in meaning, register and use, and come up with some examples that were relevant for their own use in a business context. I directed the learners towards the Cambridge Business English Dictionary Online a free resource that I enjoy using as it gives examples in a business context. It also has a built in link to a visual thesaurus.

This did meet with quite a bit of resistance at first. The learners were not comfortable with being asked to ‘research’ and there was a good bit of coaxing that needed to be done. I certainly hit the expectation barrier, where the learner wants you to ‘tell’ them the answer and does not expect to be asked to find it for themselves. I felt really quite under pressure, and did wonder if this was an appropriate activity for an in company Business English class?

I think what saved it was the fact that the research was online, it was fast and it was interesting. As soon as the learners discovered the visual thesaurus they were much happier. When they fed back to the group one of the presentations used the online thesaurus visuals to help explain:

The team that had offered the most resistance actually produced the most detailed presentation:

The set up, research and feedback for this activity took a little over 1.5 hours, including the opener with the Old English vs. Latinate words. It took longer than I had planned, but I did not see any value in rushing the learners through the activity.

On the second day of the course I asked the learners to use the online tools to improve their own texts. I had compiled a list of lexical errors from their own writing and asked them to review their word choices. This time the activity was fast and furious. The teams tore through the list and pulled together presentations to explain their new choices to the group. They also began to cherry pick other lexis, so a search on reserve and book brought up ‘to reserve judgement’, a phrase which the learners liked and wanted to start to use!

So did it work? Well the feedback from the learners said that it did. All of the learners said that one of the top three things they had learned from the session was how to use the tools to help them ‘choose their words’. They all commented that they now felt they could stop translating from French into English as their main way to choose their words. The improvement in their lexical range was marked, even though it was a short course, and the same goes for their accuracy. Using whole sentences as models was a big help here I believe.

I was happy with the outcome for the learners, I’m keen to avoid that tired ‘give a man a fish’ analogy, but it would be kind of fitting…

So what did I conclude? I was happy to see that the learners were not tempted to just follow Paul Valéry’s advice and plump for the lesser word. And I was really pleased to see the comment about translation. Why? Well, so much gets lost in translation, you see what Paul Valéry said was:

Entre deux mots il faut choisir le moindre

Which is an aphorism: ‘Mots’ sounds like ‘maux’, giving you:

Of two possible evils, choose the lesser

In my lesson I had to chose: feel unconformable for a bit and risk the learners rejecting the activity, or give in and let the learning opportunity go by. I think I chose by far the lesser of two evils.