This post is a summary of the ELTChat of January 16 2013 :

So what there is to be up in arms about?

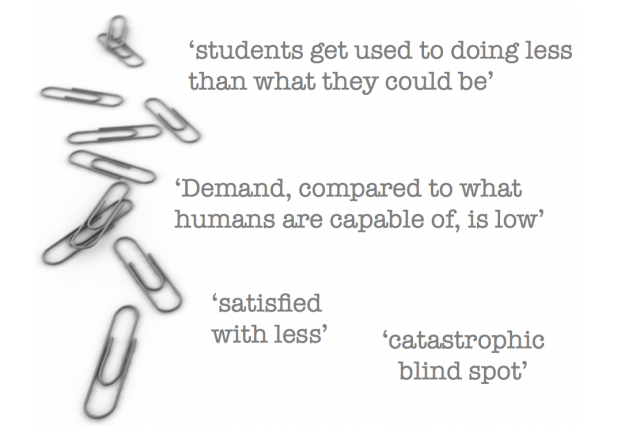

The ethos behind it is that ELT has become too lightweight, too frivolous and not rigorous enough, as I understand it. @theteacherjames

By emphasizing personalization, DHT is a critique of the ‘environment-building’ ethos of communicative language teaching @baanderson

Teachers doing just for the sake of doing @rosemerebard

In this video, part of a set of materials for a reflective seminar created by Scrivener and Underhill you hear Adrian give his ‘why’ :

And although #ELTChat could cite many examples where this was not the case, it was agreed that :

having seen lessons on 4 continents last years albeit mainly PLSes rather than mainstream I’ll stand by my ‘I agree’ @Shaunwilden

and further that

Maybe in many places teaching IS about students getting their msg across, even in poor language. DH is reaction to it @Natashetta

and even more

I’d say there’s a culture in FE that militates against Demand High: instead it requires Just Enough @pjgallantry

ELTChat’s reflections included:

It seems to me it’s about asking more from your students, pushing them further & asking them to work harder @theteacherjames

DHT is just probing a bit more and exploiting opportunities for deeper learning & LA @Marisa_C

And importantly it is method agnostic, it is a practice that can be applied however you choose to teach:

it’s about demanding “a better quality” no matter what approach or method you choose @natashetta

DH is “not anti any method, not anti-Communicative Approach, not anti-dogme, not anti-Task Based Learning.” @natashetta

Confirmation that is not a methodology, an approach or a procedure, from the Godfather of DH itself, Jim Scrivener:

DH isn’t a “method”. It’s a small (but possibly needed) course correction. A tweak. @jimscriv

a correction of what?

its an anti plateau device – its pushing that bit harder, driving the learning forward @KerrCarolyn

It’s anti letting the tail wag the dog in my opinion @dalecoulter

What does Demand High look like in practice? According to #ELTChat:

I would say the DHT comes alive mostly in feedback or exploitation not while Ss are collaborating Marisa_C

actually, my take is that DHELT means interrupting the Ss collaboration to make it more worthwhile @Imadruid

Feedback (not unearned praise) and intervention seem central to Scrivener’s view of DHT @idc74

I think its more like turning a group lesson into 121, with a focus on each individual @KerrCarolyn

Dogme – materials light, free from course-book driven learning, focus on emergent language and conversation driven, in brief @DaleCoulter

letting it all come from the learner and exploiting opportunities for learning as they arise @Marisa_C

exploiting opportunities as thy arise seems to be where the 2 have something in common – utilising ‘online’ teaching skills @dalecoulter

Breaking free of routine and automated teaching @idc74

For some they are inseparable:

Dogme without DHELT is like Pedigree Chum without the can opener @Imadruid

for others not so

can a lesson be #Dogme and not #DHElt ..yup. can it be #DHElt and not #Dogme…yup @MrChrisJWilson

One of the ‘greyer’ areas seems to around ‘learner or learning’ centric:

@jimscriv would say that DHELT is more learnING centred than learnER centred? @Imadruid

and indeed, he confirmed:

Being learning centred means you try to find just what is learner doing to do the task. You then help on to next step @jimscriv

So a kind of +1 zone approach? and personalised to that learner? @KerrCarolyn

Yes very much so. The demand is a DOABLE demand for that individual at that moment ie a focused challenge @jimscriv

doable…with help? Similar to Vygotsky’s ZPD – apprentice and expert navigate the waters of learning? @Imadruid

yes and the teacher does not abdicate his/her duty to facilitate learning @jimscriv

And hence the ‘learning’ centeredness? ‘Facilitating Learning’ is the driving force? – Spot on! @jimscriv

The ‘Dogmeticians’ of this world could now jump in and say: ‘yes but this is exactly what the ‘scaffolding’ of Dogme is all about’, and they’d be right, but the fundamental difference is a ‘material’ one:

Getting away from a slight over concern about task, material, fun etc and focussing on the learning @jimscriv

Indeed, the ‘material’ question of ‘To coursebook or not to coursebook’ is key:

The quote put a perspective that coursebook is not the problem,but how how we use coursebook. from what I read, they are in favor of it, just there is more to it @rosemerebard

Well, no. And not just because Dogme isn’t entirely anti- coursebooks, as per Dogme and the Coursebook. There are also structural differences : Dogme has a method, and techniques (as described in Teaching Unplugged and in the book of the same name). Demand High, however, is not a method. In fact, you can easily argue that ‘Demand High’ is both method and subject agnostic: it could be applied to the teaching of any subject or skill: An engineering professor or high school physics teacher could ask themselves the four key questions of Demand High

Are our learners capable of more, much more?

Have the tasks and techniques we use in class become rituals and ends in themselves?

How can we stop “covering material” and start focusing on the potential for deep learning?

What small tweaks and adjustments can we make to shift the whole focus of our teaching towards getting that engine of learning going?

And aim towards the Demand high outcomes. This is possible precisely because it is method agnostic: it is a way of reflecting that encourages reflection on and adjustment of the techniques already being used by that particular teacher.

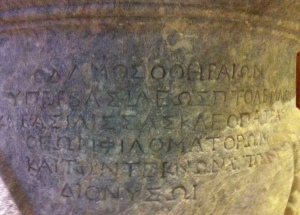

Dogme sits in the evolutionary line of Second Language Acquisition, it’s techniques could be applied to the Acquisition of any language. For me it’s immediate evolutionary predecessor was Community Language Learning and that family of methods, where the learners’ experience of the langauge is at the core.

Demand High sits in the evolutionary line of Modern Educational theory, it’s predecessors are Reflective Practice and stretch back to the thinking of John Dewey.

So if we take CLL as being the mother of Dogme, who is the father ? Well it can’t be Scott Thornbury, since he had taken a ‘vow of chastity’, but he is clearly the Godfather, guiding Dogme to adulthood. But Scott does give us the clue to its genealogy by referring back to an article which fundamentally influenced his thinking, an article on working in a materials light classroom.

The author of this important article? None other than Adrian Underhill.

Suddenly the family resemblance becomes clearer. Whether directly or indirectly, Adrian Underhill is the common denominator.

It makes me wonder who exactly was ‘running naked in the woods’ and what exactly they were up to? (I can’t help but wonder if this famous ‘tongue in cheek’ quote was referring to ‘nakedness’ as an antidote to ‘chastity’) In any case the offspring are two different but enriching ideas that are pushing Education and Language Acquisition forward:

In my opinion DHT is as valuable as Dogme or any other approach that can enhance learning effectively @toulasklavou